Archidermaptera

Fossil Dermaptera

Fabian Haas

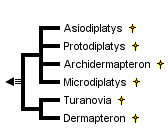

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

Archidermaptera constitute a group of fossil Dermaptera, which are known from the Upper Jurassic of Southern Kazakstan (former USSR) and from the Lower Jurassic of England (Whalley, 1985). They are marked by the retention of many primitive character states. Only a few species and specimens have been found because the enviroment of earwigs often prevents preservation. Dead animals in the soil and other crevices are rapidly degraded. So, little is known about their biology.

Interestingly, Archidermaptera have been found together with Forficulina (Vishnyakova, 1980). This suggests that the Forficulina split from the Archidermaptera earlier that the Upper Jurassic, also determing the minimum age for the whole order. It also shows that the more "modern" Forficulina did not take over at once but co-existed with the "ancient" Archidermaptera.

The suborder was erected by Bey-Bienko in 1936.

Characteristics

Although members are easily recognized as Dermapterans, the taxon is characterized only by the retention of primitive character states: antennae possess over 15 joints; ocelli present; tarsus with 4-5 segments; femora carinate; tegmina (fore wings) with distinct venation; hind wings obviously folded to a wing package (venation unknown); ovipositor long and visible in many specimens; adult cerci are long (up to body length) and with up to 40 segments.

In Recent female Forficulina the tergites of abdominal segments 8 and 9 are covered by that of segment 7, leaving only eight visible tergites. This is not so in the Archidermaptera in which all abdominal tergites are visible. The tergites overlap laterally.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The Archidermaptera were recognized as Dermaptera by their general body shape, short tegmina and wing packages longer than the tegmina. It is generally accepted that earwigs with adult segmented cerci should not be placed in the Dermaptera. Incidentally, no Archidermaptera was misplaced into another taxon, suggesting a high resemblance to extant forms and a high degree of uniformity.

The high degree of uniformity, a low number of fossils and a general consensus concerning the affinities probably prevented a cladistic analysis. It was Willmann (1990) who presented the first analysis:

=== Asiodiplatys, Microdiplatys, Protodiplatys, Archidermapteron

|

=== === Turanovia

| |

=== === Dermapteron

| |

===| === Semenviola, Semenoviolides, Turanoderma

=1=|

=== Forficulina, Hemimerina, Arixenina

The Archidermaptera comprise only the following genera: Archidermapteron, Asiodiplatys, Dermapteron, Microdiplatys, Protodiplatys and Turanovia. They are placed into one family, the Protodiplatyidae. Clearly, this is not a monophyletic group. For example, Dermapteron is closer to the Deramptera with forceps-like cerci (marked with 1 in the clade) than to Turanovia. Hence, the Archidermaptera are paraphyletic. The taxon was erected in pre-cladistic times on general similarities and not on synapomorphies.

Willmann did not include Semenviola, Semenoviolides and Turanoderma in the Forficulina; although having forceps-like cerci because they also possessed ocelli. This is considered plesiomorphic. His view is in contrast to Vishnyakova's, who included them in the Semenoviolinae, a subfamily of the Pygidicranidae, on the grounds of their forceps-like cerci.

The authors have different views what a Forficulina should be, or to say it more scientifically, which characters should be included in the ground plan of the Forficulina. Willmann considers them to have their ocelli reduced thus excluding the three genera above, while Vishnyakova holds that a Forficulina could have ocelli. It is impossible to say that Willmann's or Vishnyakova's opinion is right or wrong, they simply use different definitions for a taxon. It is therefore important to know who's definition is used and which characters they comprise to prevent misunderstanding.

Character Evolution

Although only few Archidermaptera are known, they are nonetheless interesting because they gives some clues to the sequence of character evolution.

For example, Recent Forficulina open their wings with the cerci because they fold to a wing package due to internal elasticity (Kleinow, 1966). Archidermaptera clearly had such a wing package, however, possessed long segmented (also called filiform) cerci. This implies that the unsegmented cerci of Recent Forficulina are no adaption to wing folding. The filiform cerci probably served tactile function, much like a second pair of rear antennae.

Vishnyakova (1980) described Archidermaptera with a long ovipositor. She infered that they did not build burrows for the eggs or brood, like modern Forficulina, but deposited their eggs somewhere in the soil or plant material. This also suggests, according to her, that the females did not show maternal behaviour but left the eggs alone, like most Orthoptera do. Assuming this would date the origin of the maternal care in Dermaptera to the Upper Jurassic. It would also link maternal care exclusively to the Forficulina. However, her view is somewhat speculative because no other Orthoptera show maternal care. So it is difficult to say whether or not there is a real link between the lack of ovipositor and maternal care.

References

Bey-Bienko, G.J. (1936) Dermaptères. Ed. by S. A. Sernov and A. A. Stackelberg: Faune de l'URSS L'Academie des Sciences de l'URSS, Moskau, Leningrad. 239 pp.

Kleinow, W. (1966) Untersuchungen zum Flügelmechanismus der Dermapteren. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Ökologie der Tiere, 56, 363-416.

Martynov, A. (1925) On a new interesting fossil beetle from the Jurassic beds in Northern Turkestan. Revue russe d'Entomologie, 19, 73-78.

Vishnyakova, V.N. (1980) Earwigs from the Upper Jurassic of the Karatau range. Paleontological Journal, 1, 78-95.

Whalley, P.E.S. (1985) The systematic and palaeontologeography of the Lower Jurrasic insects of Dorset, England. Bulletin of the British Museum of natural History (Geology Series), 39, 107-189.

Willmann, R. (1990) Die Bedeutung paläontologischer Daten für die zoologische Systematik. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Zoologischen Gesellschaft, 83, 277-289.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Asiodiplatys speciousus |

|---|---|

| Reference | Treatise of Invertebrate Palaeontology |

| Acknowledgements | Used with permisson from Dr. A.P. Rasnitsyn and Dr. R.L. Kaesler |

| Copyright | © 1992 Russian Academy of Science |

| Scientific Name | Dermapteron incerta |

|---|---|

| Reference | Treatise of Invertebrate Palaeontology |

| Acknowledgements | Used with permisson from Dr. A.P. Rasnitsyn and Dr. R.L. Kaesler |

| Copyright | © 1992 Russian Academy of Science |

About This Page

I am grateful to Dr. RD Briceño and Mr. G Simpson for helpful comments on the manuscript. I am also grateful to Dr. AP Rasnitsyn and Dr. RL Kaesler for permitting the use of figures.

Fabian Haas

Institut für Spezielle Zoologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Jena, Germany

Page copyright © 1996

All Rights Reserved.

Citing this page:

Haas, Fabian. 1996. Archidermaptera. Fossil Dermaptera. Version 01 January 1996 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Archidermaptera/10379/1996.01.01 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site