Amniota

Mammals, reptiles (turtles, lizards, Sphenodon, crocodiles, birds) and their extinct relatives

Michel Laurin and Jacques A. Gauthier

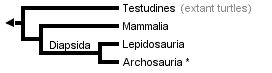

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxPhylogeny modified from Laurin & Reisz (1995) and Lee (1995); the position of Mesosauridae follows Modesto (1999). Node names follow Gauthier et al. (1988b) and Gauthier (1994). The position of turtles (Testudines) is uncertain; some authors place them approximately in the position shown above (Laurin & Reisz, 1995; Lee, 1993, 1995, 2001; Frost et al., 2006; Werneburg & Sánchez-Villagra, 2009; Lyson et al. 2010), while others place them among Diapsida (deBraga & Rieppel, 1996, 1997; Rieppel & Reisz, 1999; Hedges & Poling, 1999; Mannen & Li, 1999; Hugall et al., 2007; Li et al., 2008).

Introduction

Amniotes include most of the land-dwelling vertebrates alive today, namely, mammals, turtles, Sphenodon, lizards, crocodylians and birds. It is a diverse clade with over 20000 living species. Amniotes include nearly all of the large plant- and flesh-eating vertebrates on land today, and they live all over the planet in virtually every habitat. They also sport disparate shapes - chameleons, bats, walruses, Homo sapiens, soft-shelled turtles, ostriches and snakes are but a few examples - and they include some of the smallest (sphaerodactyline geckoes) and largest (mysticete whales) vertebrates (Figs. 1 and 2). Although fundamentally land dwellers, several clades such as ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, pinnipeds and cetaceans have returned to the sea. A few forms are gliders - including the Flying Dragon lizards, the Sugar Glider, Flying Squirrels and some gliding snakes - and powered aerial flight has originated three separate times, first in pterosaurs, then in birds, and later still in bats.

Figure 1. Two extant amniotes (diapsids). The rattlesnake can detect its prey at night using an infrared-sensitive organ that allows it to detect the warm body of small mammals. It then kills its prey with it poisonous fangs. Parrots eat nuts and fruits. Pictures copyright © 1996 Michel Laurin.

An extensive fossil record documents the origin and early evolution of Amniota, and that record has played a key role in understanding phylogenetic relationships among the living amniotes (Gauthier et al., 1988b). The oldest amniotes currently known date from the Middle Pennsylvanian locality known as Joggins, in Nova Scotia (Carroll, 1964). The relationships of these fossils indicate that amniotes first diverged into two lines, one line (Synapsida) that culminated in living mammals, and another line (Sauropsida) that embraces all the living reptiles (including birds). One Joggins fossil, the "protorothyridid" Hylonomus, appears to be a very early member of the line leading to Sauria (Crown-clade diapsids), the clade encompassing all living diapsids. This suggests that the more inclusive clade of which turtles (Testudines) are part (Anapsida) in most morphological phylogenies had diverged as well, even though its current record extends back only to the Lower Permian (Laurin & Reisz, 1995).

An older amniote (from the Lower Carboniferous) was reported (Smithson, 1989). However, more recent studies suggested that it was only a close relative of amniotes (Smithson et al., 1994), and the latest study even suggested that it was more likely to be a stem-tetrapod or an early amphibian than a relative of amniotes (Laurin & Reisz, 1999).

Figure 2. More extant amniotes. The insectivorous elephant shrew (a synapsid) resembles vaguely the earliest placental mammals. The omnivorous terrestrial box turtle Terrapine (an extant anapsid) eats mushrooms, fruits, insects, and worms. Like all turtles, it is not affected by senescence but eventually succumbs to a disease, an accident, or a predator. Pictures copyright © 1996 John Merck.

Characteristics

Many amniote synapomorphies are widely interpreted as adaptations to the rigors of life on land. Indeed, Amniota owes its name to what may be its most distinctive attribute, a large "amniotic" egg. While most of us are most familiar with the hard-shelled eggs found in birds, Stewart (1997) showed that the first amniotic eggs probably had a flexible outer membrane, and that a mineralized (but still flexible) outer membrane is a synapomorphy of reptiles. The heavily mineralized, hard shell is a synapomorphy of archosaurs (crocodiles and birds), and it also appeared at least three times in turtles, and a few times in squamates. This probably explains why the oldest known amniotic egg (Coyne, 1999) only dates from the Lower Triassic (220 My), whereas the oldest amniote dates from the Upper Carboniferous (310 My); the eggs of most (if not all) Paleozoic amniotes must have had a flexible, poorly mineralized or unmineralized outer membrane, and thus had a low fossilization potential (Laurin, Reisz & Girondot, 2000).

The amniotic egg possesses a unique set of membranes: amnion, chorion, and allantois (Fig. 3). The amnion surrounds the embryo and creates a fluid-filled cavity in which the embryo develops. The chorion forms a protective membrane around the egg. The allantois is closely applied against the chorion, where it performs gas exchange and stores metabolic wastes (and becomes the urinary bladder in the adult). As in other vertebrates, nutrients for the developing embryo are stored in the yolk sac, which is much larger in amniotes than in vertebrates generally. Hatchling amniotes also possess an egg-tooth and horny caruncle on the snout tip to facilitate exit from their hard-shelled eggs. The amniotic egg, together with a penis for internal fertilization, loss of a free-living larval stage in the life cycle, and the ability to bury their eggs, enabled amniotes to escape the bonds that confined their ancestors' reproductive activities to aquatic environments. It has been suggested that the original function of the extra-embryonic membranes of the amniotic egg was to facilitate interactions between the mother and the embryo (Lombardi, 1994), but this hypothesis is not supported by the distribution of extended embryo retention in vertebrates, according to most proposed phylogenies (Laurin & Girondot, 1999). Some components of the amniotic egg have been variously modified within Amniota. Placental mammals, for example, have suppressed the egg shell and yolk sac, and elaborated the amniotic membranes to enable nutrients and wastes to pass directly between mother and embryo.

Figure 3. Development of extraembryonic membranes in an amniote egg (chick). In this early developmental stage, the yolk sac is expanding over the yolk. The amnion and chorion are expanding over the embryo and will eventually form the amniotic chamber. The allantois is expanding toward the chorion, with which it will form a respiratory membrane, in addition to storing metabolic wastes of the embryo. Redrawn from Campbell (1993). Copyright © 1996 Michel Laurin.

The comparative aridity of the terrestrial environment affects all aspects of amniote biology, and not just their reproductive systems. Thus, amniotes have a relatively impervious skin that reduces water loss. They also possess horny nails that, among other things, enable them to use their forelimbs to dig burrows into which they can retreat during the heat of the day. The imperative to reduce water loss is equally evident in the density of renal tubules in the metanephric kidney of amniotes, in the larger size of their water-resorbing large intestines, and in the full differentiation of the Harderian and lacrimal glands in the eye socket whose antibacterial secretions help to moisten and, along with a third eyelid (the nictitans), to further protect the eye from desiccation. The commitment of amniotes to a life on land is also revealed by an extensive system of muscle stretch receptors that enables finer coordination and greater agility during locomotion, their enlarged lungs (which are the only remaining organs of gas exchange owing to the loss of gills), and the complete loss of the lateral line system other vertebrates use to detect motion in water.

Many of these features are rarely preserved in fossils, but there are some novelties in the skeleton that are no less diagnostic of amniotes. For example, amniotes have at least two pairs of sacral ribs, instead of just one pair. They also have an astragalus bone in the ankle, instead of separate tibiale, intermedium, and proximal centrale bones. Finally, they have paired spinal accessory (11th) and hypoglossal (12th) cranial nerves incorporated into the skull, in addition to the ten pairs of cranial nerves present in amphibians.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Generations of systematists have studied amniote phylogeny at diverse genealogical levels, and until a few years ago, its broad outlines were thought to be reasonably well understood. Indeed, recognition of the major living clades, such as mammals, turtles and birds, antedates the Theory of Descent. Relations among these taxa, and especially the connections of various fossils to them, have been contentious in post-Darwinian times. Much of that controversy can, however, be attributed to the fact that during the first two-thirds of this century, there was little thought given to what constituted evidence for phylogenetic relationships. The origins of the major extant lines of Amniota have become clearer in the post-Hennigian era. Nevertheless, the precise relations of a number of clades, most notably the turtles among extant forms and the aquatic and highly divergent ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians among extinct forms, remain contentious.

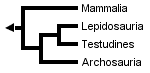

Early phylogenetic analyses placed turtles outside of the remaining amniotes (only crown-clade names are listed to simplify the trees):

* Major living amniote clades after Gaffney (1980).

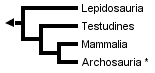

Gauthier et al. (1988a, b, and c) later placed turtles as the sister clade to Sauria (crown-diapsids), and this topology has now gained wide acceptance, at least among morphologists and paleontologists:

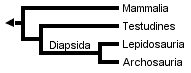

However, Rieppel (1994, 1995), Rieppel & deBraga (1996) and deBraga & Rieppel (1997) have suggested that turtles may be the sister clade to lepidosaurs. This requires that turtles are saurians who have lost both the upper and lower temporal fenestrae (holes in the skull associated with jaw muscles) so diagnostic of diapsid reptiles:

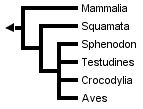

The three trees presented above include only extant taxa, and many phylogenetic analyses of amniotes have ignored extinct taxa. However, it is important to bear in mind that discovering the globally most parsimonious tree requires the inclusion of extinct taxa in a phylogenetic analysis (Gauthier et al., 1988b). Without fossils, the best-supported tree for amniotes inferred from morphological data is the following (although only one more step is required to switch the positions of lepidosaurs and turtles):

* Tree based on living amniotes only (after Gauthier et al., 1988b).

Recent molecular evidence for amniote relationships conflicts with paleontological and morphological evidence. Initially, some gene sequences suggested a close relationship between birds and mammals, although never with strong statistical support (e.g., Bishop & Friday, 1987; Goodman et al., 1987; Hedges et al., 1990). More recently, a study of the molecular evidence for the origin of birds (15 genes; 5280 nucleotides, 1461 amino acids) discovered strong support (100% bootstrap P value, BP) for a close relationship between birds and crocodilians (Hedges, 1994). A smaller data set of 11 transfer RNA genes (686 sites) also resulted in a bird-crocodilian grouping (Kumazawa & Nishida, 1995). A basal position for mammals was supported (99% BP) by analysis of a 3 kilobase portion of the mitochondrial genome containing the two ribosomal RNA genes (Hedges, 1994). In the same study, a Sphenodon-squamate relationship also was found, but support for that grouping and for the position of turtles was not very strong.

The most recent molecular phylogenies have generally placed turtles among archosauromorphs, and often within archosaurs (Mannen et al., 1997; Mannen & Li, 1999; Hedges & Poling, 1999; Hugall et al., 2007). The latter placement is the least compatible with the morphological evidence, and no convincing explanation has been found so far to explain this discrepancy.

At least two total evidence analyses (in which molecular and morphological data are combined) suggest that turtles are not diapsids (Lee, 2001; Frost et al., 2006). In both, the molecular characters are much more numerous than the morphological ones, which implies significant support for the placement of turtles outside diapsids in these molecular datasets.

Many gene sequences of birds and mammals exist, but the relatively small number of sequences from representatives of other amniote lineages, especially tuataras (Sphenodon) and turtles, has hindered the estimation of a robust molecular phylogeny for all major groups of living amniotes. This is reflected by the low resolution of the molecular phylogeny obtained by Hedges & Poling (1999) when Sphenodon (using only sequences of genes available in Sphenodon) was included:

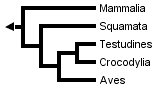

Without Sphenodon and using the greater number of sequences available for other taxa, Hedges & Poling obtained the following fully resolved phylogeny, in which turtles are the sister-group of crocodilans:

Developmental data has rarely been used to study this question, but it has recently been found to place turtles outside diapsids (Werneburg & Sánchez-Villagra, 2009).

If extinct amniotes are considered, the phylogeny is much more complex and controversial. Formerly, captorhinids were believed to be closely related to turtles (Gauthier et al., 1988b, c), but more recently, several groups of parareptiles have been sugested as closest relatives of turtles, such as procolophonids (Reisz & Laurin, 1991; Laurin & Reisz, 1995), pareiasaurs (Lee, 1993, 1994, 1995, and 1996), and Eunotosaurus (Lyson et al., 2010). Some paleontologists (Rieppel, 1994, 1995; Rieppel & deBraga, 1996; deBraga & Rieppel, 1997) place turtles among diapsids, especially as the sister-group of euryapsids (a group of Mesozoic marine diapsids). The linked page Phylogeny and Classification of Amniotes provides information about the phylogenies incorporating extinct amniote taxa, and provides a detailed classification of the relevant groups. The linked page Temporal Fenestration and the Classification of Amniotes discusses how temporal fenestration has been used to classify amniotes, and how tempororal fenestration evolved.

References

Bishop, M. J., & A. E. Friday. 1987. Tetrapod relationships: the molecular evidence. In Patterson, C (ed.) Molecules and Morphology in Evolution: Conflict or Compromise?: 123-139. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Campbell, N. A. 1993. Biology. 3rd edition. New York: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing.

Carroll, R. L. 1964. The earliest reptiles. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 45: 61-83.

Coyne M. 1999. World's oldest reptile nest found. Marine Turtle Newsletter 83: 21.

deBraga M. & O. Rieppel. 1997. Reptile phylogeny and the interrelationships of turtles. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 120: 281-354.

Frost D. R., T. Grant, J. Faivovich, R. H. Bain, A. Haas, C. F. B. Haddad, R. O. de Sá, A. Channing, M. Wilkinson, S. C. Donnellan, C. J. Raxworthy, J. A. Campbell, B. Blotto, P. Moler, R. C. Drewes, R. A. Nussbaum, J. D. Lynch, D. M. Green, & W. C. Wheeler. 2006. The amphibian tree of life. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 297: 1–370.

Gaffney, E. S. 1980. Phylogenetic relationships of the major groups of amniotes. In A. L. Panchen (ed.) The Terrestrial Environment and the Origin of Land Vertebrates: 593-610. London: Academic Press.

Gauthier, J. A. 1994. The diversification of the amniotes. In D. R. Prothero and R. M. Schoch (ed.) Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution: 129-159. Knoxville: The Paleontological Society.

Gauthier J., R. Estes, & K. de Queiroz. 1988a. A phylogenetic analysis of Lepidosauromorpha. In: R. Estes and G. Pregill (eds.) Phylogenetic relationships of the lizard families: 15-98. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gauthier, J., A. G. Kluge, & T. Rowe. 1988b. Amniote phylogeny and the importance of fossils. Cladistics 4: 105-209.

Gauthier, J., A. G. Kluge, & T. Rowe. 1988c. The early evolution of the Amniota. In M. J. Benton (ed.) The phylogeny and classification of the tetrapods, Volume 1: amphibians, reptiles, birds: 103-155. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Goodman, M., M. Miyamoto, & J. Czelusniak. 1987. Pattern and process in vertebrate phylogeny revealed by coevolution of molecules and morphologies. In C. Patterson (ed.) Molecules and Morphology in Evolution: Conflict or Compromise?: 141-176. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hedges, S. B. 1994. Molecular evidence for the origin of birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91:2621-2624.

Hedges, S. B., K. D. Moberg, & L. R. Maxson. 1990. Tetrapod phylogeny inferred from 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA sequences and a review of the evidence for amniote relationships. Molecular Biology and Evolution 7:607-633.

Hedges S. B. & L. L. Poling. 1999. A molecular phylogeny of reptiles. Science 283: 998-1001.

Hugall A. F., R. Foster, & M. S. Y. Lee. 2007. Calibration choice, rate smoothing, and the pattern of tetrapod diversification according to the long nuclear gene RAG-1. Systematic Biology 56: 543–563.

Kumazawa, Y., & M. Nishida. 1995. Variations in mitochondrial tRNA gene organization of reptiles as phylogenetic markers. Molecular Biology and Evolution 12:759-772.

Laurin, M. & R. R. Reisz. 1995. A reevaluation of early amniote phylogeny. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 113: 165-223.

Laurin M. & M. Girondot. 1999. Embryo retention in sarcopterygians, and the origin of the extra-embryonic membranes of the amniotic egg. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, Zoologie, Paris, 13e SÈrie 20: 99-104.

Laurin M. & R. R. Reisz. 1999. A new study of Solenodonsaurus janenschi, and a reconsideration of amniote origins and stegocephalian evolution. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 36: 1239-1255.

Laurin M., R. R. Reisz, & M. Girondot. 2000. Caecilian viviparity and amniote origins: a reply to Wilkinson and Nussbaum. Journal of Natural History 34: 311-315.

Lee, M., S. Y. 1993. The origin of the turtle body plan: bridging a famous morphological gap. Science 261: 1716-1720.

Lee, M. The turtle's long-lost relatives. Natural History, April 1994, 63-65.

Lee, M. S. Y. 1995. Historical burden in systematics and the interrelationships of 'Parareptiles'. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 70: 459-547.

Lee M. S. Y. 1996. Correlated progression and the origin of turtles. Nature 379: 812-815.

Lee M. S. Y. 2001. Molecules, morphology, and the monophyly of diapsid reptiles. Contributions to Zoology 70: 1-18.

Li C., X.-C. Wu, O. Rieppel, L.-T. Wang, & L.-J. Zhao. 2008. An ancestral turtle from the Late Triassic of southwestern China. Nature 456: 497–501.

Lombardi J. 1994. Embryo retention and evolution of the amniote condition. Journal of Morphology 220: 368.

Lyson T. R., G. S. Bever, B.-A. S. Bhullar, W. G. Joyce, & J. A. Gauthier. 2010. Transitional fossils and the origin of turtles. Biology Letters 6: 830–833.

Mannen H., S. C.-M. Tsoi, J. S. Krushkal, W.-H. Li, & S. S.-L. Li. 1997. The cDNA cloning and molecular evolution of reptile and pigeon lactate dehydrogenase isozymes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 14: 1081-1087.

Mannen H. & S. S.-L. Li. 1999. Molecular evidence for a clade of turtles. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 13: 144-148.

Modesto S. P. 1999. Observations on the structure of the Early Permian reptile Stereosternum temidum Cope. Palaeontologia Africana 35: 7-19.

Reisz, R. R., & M. Laurin. 1991. Owenetta and the origin of turtles. Nature 349: 324-326.

Rieppel, O. 1994. Osteology of Simosaurus gaillardoti and the relationships of stem-group sauropterygia. Fieldiana Geology 1462: 1-85.

Rieppel O. 1995. Studies on skeleton formation in reptiles: implications for turtle relationships. Zoology-Analysis of Complex Systems 98: 298-308.

Rieppel O. & M. deBraga. 1996. Turtles as diapsid reptiles. Nature 384: 453-455.

Rieppel O. & R. R. Reisz. 1999. The origin and early evolution of turtles. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 30: 1-22.

Smithson T. R. 1989. The earliest known reptile. Nature 342: 676-678.

Smithson T. R., R. L. Carroll, A. L. Panchen, & S. M. Andrews. 1994. Westlothiana lizziae from the VisÈan of East Kirkton, West Lothian, Scotland, and the amniote stem. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 84: 383-412.

Stewart J. R. 1997. Morphology and evolution of the egg of oviparous amniotes. In: S. Sumida and K. Martin (ed.) Amniote Origins-Completing the Transition to Land (1): 291-326. London: Academic Press.

Werneburg I. & M. R. Sánchez-Villagra. 2009. Timing of organogenesis support basal position of turtles in the amniote tree of life. BMC Evolutionary Biology 9: 9 pages.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Proganochelys |

|---|---|

| Location | Germany |

| Comments | Restored environment of Proganochelys (the oldest known turtle) during the Late Triassic in Germany. Besides Proganochelys, small hybodont sharks are shown. |

| Creator | Painting by Frank Ippolito |

| Specimen Condition | Fossil -- Period: Late Triassic |

| Copyright | © 1987 American Museum of Natural History |

About This Page

We thank Drs. David Maddison and Katja Schulz for many useful comments on this page, and Ms. Patricia Lai for proof-reading the text.

Michel Laurin

Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France

Jacques A. Gauthier

Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Michel Laurin at

michel.laurin@mnhn.fr

Page copyright © 2012 Michel Laurin and Jacques A. Gauthier

Page: Tree of Life

Amniota. Mammals, reptiles (turtles, lizards, Sphenodon, crocodiles, birds) and their extinct relatives.

Authored by

Michel Laurin and Jacques A. Gauthier.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Amniota. Mammals, reptiles (turtles, lizards, Sphenodon, crocodiles, birds) and their extinct relatives.

Authored by

Michel Laurin and Jacques A. Gauthier.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- Content changed 30 January 2012

Citing this page:

Laurin, Michel and Jacques A. Gauthier. 2012. Amniota. Mammals, reptiles (turtles, lizards, Sphenodon, crocodiles, birds) and their extinct relatives. Version 30 January 2012. http://tolweb.org/Amniota/14990/2012.01.30 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site